His beer glass was filled to the brim, except it wasn't beer that sat in his glass, instead, it was coffee. Malcolm Holcombe took drag after drag on his cigarettes before he would fall under the spell of acoustic guitar. He was possessed by every note, wavering between soul searching harmony and life torn ferocity.

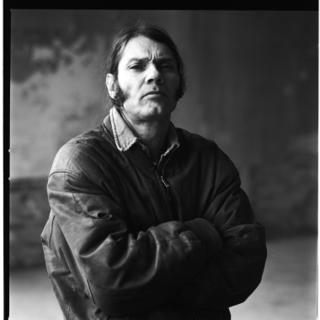

His beer glass was filled to the brim, except it wasn't beer that sat in his glass, instead, it was coffee. Malcolm Holcombe took drag after drag on his cigarettes before he would fall under the spell of acoustic guitar. He was possessed by every note, wavering between soul searching harmony and life torn ferocity.Holcombe and his two acoustic guitars shared a bond, visible on the surface--they both had signs of extreme wear and tear, but the sound they made together was jaw dropping. A native of North Carolina, Holcombe was seated on the stage at Schubas almost as if he were some pan handler asking for change on a street corner. His face was the pure definition of rustic; the body seemed frail under his clothes, but his eyes conveyed a toughness in his soul that could not be broken. What started as three people in a room for an early 7:30 P.M. show turned into a strong group of fans that entered the room the second his voice hit the microphone. The captive audience hung on every word Holcombe sang in his gravely, baritone voice, weathered by age. To those that follow the country/folk scene, Holcombe is highly regarded as a fascinating poet schooled in the blues, bluegrass, and Appalachian song traditions.

The thirty years Holcombe has been playing music came across with each song he picked out of his head. He had no setlist made. He simply asked the soundman to yell out when his set time was almost up and that was it. Someone in the audience would yell out a request ("Dressed In White") and Holcombe would deliver. There was no arrogance about him. He was clearly grateful for the warm applause that showered him after each song and each voice that spoke up from out of the darkness to request a song.

If there is beauty to sadness, then Holcombe has his finger squarely on its pulse. The muse that speaks to Holcombe is not a single voice. Between songs Holcombe would talk about the voices that he hears in his mind. The audience laughed but there was a feeling that Holcombe wasn't quite joking. He talked about these voices as one hundred naked women. "My mind plays tricks in the silence," confessed Holcombe during "I Never Heard You Knocking." With those words, Holcombe painted the picture of a person that would "mumble" and "stutter" in the night. It was a moment where the artist really reflected the art. The music provided his own sort of sanity. Each song became a kind of escape into a story, a different world, and then, after the last note, Holcombe would return to the audience a quiet, humble man.

If there is beauty to sadness, then Holcombe has his finger squarely on its pulse. The muse that speaks to Holcombe is not a single voice. Between songs Holcombe would talk about the voices that he hears in his mind. The audience laughed but there was a feeling that Holcombe wasn't quite joking. He talked about these voices as one hundred naked women. "My mind plays tricks in the silence," confessed Holcombe during "I Never Heard You Knocking." With those words, Holcombe painted the picture of a person that would "mumble" and "stutter" in the night. It was a moment where the artist really reflected the art. The music provided his own sort of sanity. Each song became a kind of escape into a story, a different world, and then, after the last note, Holcombe would return to the audience a quiet, humble man.The song that really captured Holcombe as a person and a musician was a sweet song of thankfulness called "Doin' His Job." Its message was simple and to the point, "Thank you sweet Lord for my job." His voice carried a weariness that could be felt throughout the room. But it wasn't a tale of struggles or defeats. As Holcombe sang each line, you felt as though he was letting off a sigh, proud of the work he has done and aware of the chances he's been given. Whatever was insurgent country about Holcombe that night was unnoticeable. His style of play, inspired and sharp, and manic vocals were not revolts against what would be thought of as country establishment; they were just the roots of a genre that has been glossed over for commercialism. If Tom Waits, John Prine, and Bob Dylan had lived during the Dust Bowl of the 1930s, then Malcolm Holcombe would be the culmination of all three.

Malcolm Holcombe was just doing his job playing music without any reservations. When the night concluded, he and the audience had made a special night.

No comments:

Post a Comment